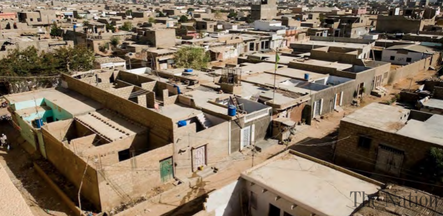

Slums

Karachi, Pakistan 2018

In Mike Davis’ book Planet of Slums the efforts of major global cities to veil their slums is revealed. Davis brings the prevalence of slums to our attention, from their slow development during the colonial era, when country natives were not allowed property in the cities, to the vast expansion of slums in the latter 20th century due to post-independence neoliberal policies that displaced rural populations but neglected adequate housing infrastructure in the cities. A slum is essentially a densely populated area where people created their own housing and livelihood after their states have abandoned them. Self-created housing is substandard and often lacks services such as water, electricity, and sanitation. Slums are much like a city within a city, where inhabitants establish informal housing and informal businesses to create their informal economy even as they contribute to the urban economy as a whole. The needs of the slum residents are largely ignored when officials, who are often pressured by IMF and World Bank lenders, are faced with whether to raise taxes on the wealthy or cut social programs; the interest of the elites take precedence. Often, people of the slums are only noticed as an eyesore that must be hidden during international events or cleared for investment opportunities. Crimes and resistance accusations are some justifications that governments use to allow their military or contracted paramilitary in to forcefully remove people from slum communities that happen to be located on what has become prime realty space. Some are relocated to poorly made housing developments far from their work; others are left to fend for themselves. As we will see in another page of this project, the rich wall themselves away behind electric or concrete fences and commute by expressways that guard them from the poor. The elite are not citizens of their country as they live in a utopian “off world” while the people of the country work tirelessly for their right to the city.

Karachi is Pakistan’s most populated city that rests on its southern coast is no stranger to slums. Express Tribune reported in their article “Karachi up top, but not my much,” that the most recent census in 2017 shows the population to be 14.9 million. Of these 14.9 million people, 62 percent live in katchi abadis, a term used for the informal housing built in slum settlements. These settlements rest on only 5.5 percent of the urban land of Karachi. High population density is a concern for the city as many slum residents are now beginning to build multiple stories for more space, as reported in the Pakistan Press International in 2015. Ramzan Chandio estimates in his article, whose title, “50 slums on 876 acres of govt land,” captures this very point that Karachi has about 539 slum settlements and 50 of those settlements stretch over 876 acres of government land. A number of slums have been regularized by the government, deeming them legal settlements and protecting them from being demolished, as reported in 2009 by The Nation in the article “Katchi Abadis People to Get Ownership Rights.” Still many slum settlements are considered illegal and are not protected from being cleared away to make space for urban development. Jane Perlez writes in her 2010 New York Times article titled “Karachi Turns Deadly, Diverted by Bitter Rivalries in Pakistan,” that slum settlements are most dense in Orangi Town and Lyari where sanitation and electricity are scarce.

In “Land Contestation in Karachi and the Impact on Housing and Urban Development,” Arif Hasan (2015) lays the foundation of how land has been distributed in post-colonial Karachi. Hasan explains the political conflict between two major political parties: Mutahida Quomi Movement (MQM), which represents the Urdu speaking population of Karachi made up of migrants from India; and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), which represents the Sindhi speaking population of Karachi. The population boom came from migrants and refugees to the area, which the government tried to manage. Housing developments were created on the outskirts of the city where jobs were promised but never realized, transforming this high density, ethnically diverse, and multi-class city into a city of low density sprawl with divisions in class and ethnicity. Informal housing grew exponentially. Hasan also tells us that 38 percent of the Karachi population resides on 74 percent of city land that has been formally developed, whereas 62.2 percent of the population resides on only 22 percent of the land that has been informally developed. This starkly shows the inequality of housing and land use in Karachi. Karachi’s Arabian Sea shores are being dedicated to more hotels for tourists and transnational business visitors and luxury apartment living, giving less use to the poorer residents of Karachi.

“Sustainable Harnessing of the Surface Water Resources for Karachi,” by Irfan and colleagues is an important discussion about the water shortage crisis in Karachi and possible solutions. This water crisis is due in part by climate change, shortage of fresh water sources, and the rapid urbanization in recent decades in Karachi. In 2009 it was estimated that the city needs 853 million gallons per day (mgd) but the city was supplying only 630 mgd. In 2017 the demand has risen to 1250 mgd with only 50% of that being supplied. Karachi is not a master planned city and having no water supply plan has been detrimental to the city. More city planning needs to be done and the development of small dams on the Mol and Khadeji Rivers may help solve the water shortage.

Katchi abadis are faced with both a water shortage problem and a flooding problem. Monsoon season brings heavy rains. As Amar Guriro shares in his 2017 article “Exploring why Karachi’s rainwater has nowhere to go,” due to the city’s mismanagement of trash disposal, garbage block the natural stormwater drains. This blockage prevents the rainwaters from draining into the Layari or Malir rivers, which would eventually drain out into the Arabian Sea, diverting it away from the city. Informal housing continues to grow as climate refugees, who leave their homes due to droughts impacting their farms, move into the city to seek work. Flooding is a devastating consequence for the slum residents. Over 20 people, including children, died in the August 2017 monsoon flooding. Clearing out the drains will lessen the severity of the floods.

Garbage is not only in the stormwater drains; it is prevalent throughout the city, not only in katchi abadis but in middle and elite class areas as well. Nadeem Paracha details the history of the garbage problem in Karachi in his 2017 article “A history of Karachi’s garbage outbreaks,” and brings to our attention how serious a problem it is. The political parties MQM and PPP are struggling to manage this waste disposal problem. The PPP have imported garbage trucks from China while the MQM has initiated city clean-up and beautification campaigns, yet the problem still exists. Paracha reports that Malik Riaz, a real estate tycoon and philanthropist, donated millions of rupees to have mountains of garbage removed from the city. Much of the sprawl of Karachi is unplanned and the management of waste disposal has been severely neglected.

Many people have relocated to Karachi in an attempt to flee from wars, climate changes, and poor economic conditions hoping for an opportunity in the city. Karachi has failed to provide the necessary services to accommodate this influx of migrants. Political parties battle for votes by making promises, but are minimally helping those who suffer in katchi abadis. As in many other cities across the globe, Karachi’s slums are a consequence of a globalized city that has been influenced by neoliberal policies that benefit an elite few at the top while starving the lower classes.