Walking in the City

Karachi, Pakistan 2018

In Tsung-yi Michelle Huang’s book Walking Between Slums and Skyscrapers, dual compression is the amalgamation of two compressing forces: global and local. Vernacular city spaces are collapsing to create space for the enormous presence of global capital in the Asian global cities she analyzes. The creation of this global space means the destruction of local urban space. Along with skyscrapers designed by international architects, high-end glamour zones, and transnational corporate headquarters comes the need for immigrant labor to fill the low-end of the labor force serving these global enterprises. Public housing crams the city’s inhabitants into condensed living spaces. But behind the guise of philanthropy as housing offered to city residents Huang sees the master plan of land redistribution. The vernacular architecture and culture are squeezed out of prime city spaces to give room to higher value commercialism. For Huang, the forces of globalization evade time and place by collapsing the two. Clones of skylines emerge as monumental skyscrapers appear all over the global urban sphere.

In an attempt to escape the pressures of dual compression, city inhabitants walk the city for a sense of free movement and open space. Huang analyzes the film Chungking Express to interpret the experience of Hong Kong’s residents walking between slums and skyscrapers. City dwellers walk among these global establishments hoping that one day they too will achieve the wealth and space that transnational companies enjoy. Chungking Mansion is the architectural manifestation of global compression. This congested beehive building bustling with people from multiple ethnic backgrounds, who live and conduct business within its cramped pockets of space. In a city with so many people in close proximity, Hong Kong is still not without loneliness.

Time-space compression is a very compelling concept. Transnational architecture supersedes the vernacular architecture, creating anonymity, a placeless structure. This ties into previous discussions of the global elite being a people without a country, connected only with each other and the network of transnational commerce that roots down in global cities. Like the Disneyland erected in what was once a peaceful getaway for Hong Kong residents, global forces find their way into the city, erasing what was once there, blurring lines of history and space. The magic of globalization is only offered to an elite populace while the majority walks through the small slices of space left for them. Part One of Huang’s book is titled Hong Kong Blue: Where Have All the Flaneurs Gone? Walking in Between Eternal Dual Compression. The term eternal implies that which exists without a beginning or an end. Forms of oppression have always existed and in contemporary times it is a near form of imperialist commercialism represented by palatial skyscrapers and high-end shopping centers; these exist without a sell-by date and dizzy the flaneur who tried to make their way through the compressed time-space he or she exists in.

Karachi too appears to be experiencing the same kind of global and local compression that Huang describes for Hong Kong. Karachi residents experience the global compression as transnational planners redesign the city’s landscape for gated communities and high rise luxury living that most Karachiites cannot afford to enjoy. And Karachi residents who live along the shore find themselves being pushed out as transnational corporations building offices and luxury towers along the Arabian Sea shores, encroaching on lands long held by fishermen.

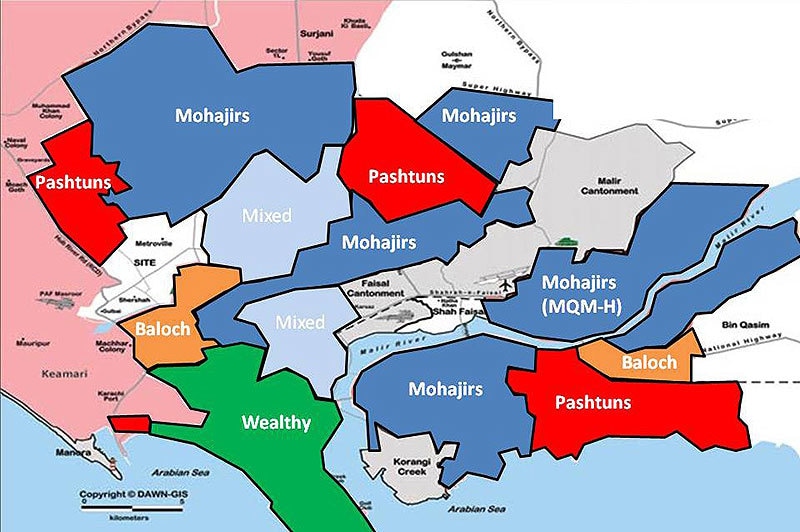

But Karachi residents also experience a different kind of local compression, a form of sectarian compression. Due to the migration into Karachi from many parts of South Asia, many diverse pockets of the city are inhabited by religious or ethnic majorities who dominate their sections of the city. Few neutral zones exist. Diversity in a city is often regarded as beneficial and this holds for Karachi, which is more socially liberal than many parts of Pakistan because no one group can dominate the entire city. However, city inhabitants do experience distress from sectarian compression. Nadeem F. Paracha shares the friction of this compression in his 2015 article, “Understanding Karachi and the 2015 local elections.” The separated neighborhood clusters, defined by their ethnicity, religion, or class often experience sectarian violence and strife due to one group claiming another group is encroaching on their claims to urban land. Karachi’s neutral spaces are more transnationalized, with multinational organizations, factories, major malls, and entertainment centers. State organizations and a larger government presence are also seen in the neutral zones, which maintain more peaceful coexistence than do the sectarian zones of conflict.

Paracha explains that Pakistan’s major political parties typically represent a group but in order to win elections they must appeal to all the people. For example, Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) represents the Mohajir ethnic population of Karachi but to win elections they keep a fairly liberal platform. Political parties other than MQM with a strong presence in Karachi include Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI), Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP), Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PML-N), Awami National Party (ANP) and others. The political parties of Karachi have great influence over their parts of the city. This issue is complicated and goes beyond the scope of this website to detail in full.

Watch this PBS video about sectarian violence in Karachi to learn more

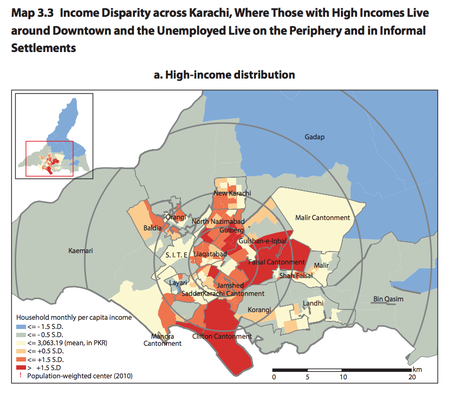

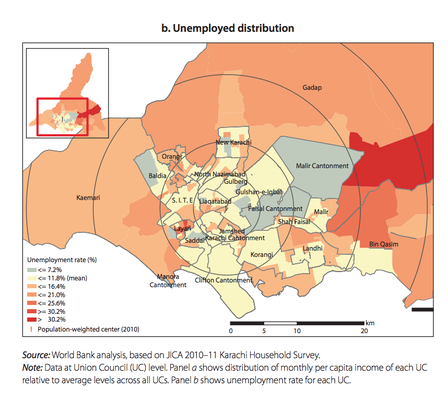

The following graphics by the World Bank show income inequality in Karachi

In addition to the city’s sectarian fragmentation, there is great contention in Karachi’s streets as to who has the right to the roadways. Some argue that eateries and vendors are illegally encroaching on the main streets, resulting in blocked traffic. Local police are accused of allowing this as they patronize the informal business encroachments, reports the Pakistani Press International in their 2018 article titled "Traffic cops helpless as eateries occupy service road." It is unclear whether those arguing against the encroachments are doing so for genuine concern for the flow of traffic and well being of the citizens or because encroachment businesses are unsightly and ward off the upper class from the city areas experiencing local compression.

In “The Need for Speed: Traffic Regulation and the Violent Fabric of Karachi,” Laurent Gayer examines traffic flow as a means of control over the city of Karachi. Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), the dominating political force in Karachi since the 1980’s, uses its force to regulate traffic flow in the city as a way to assert its authority. MQM has accomplished this through two opposing means. Accelerating traffic flows to benefit their affluent constituents and conversely impeding traffic flows to shut down the city when necessary. Contending with control over traffic flows is an important part of daily life for Karachiites who commute for work.

With sectarian compression and influences from political parties, city officials, and transnational corporations and developers, it is hard to determine who has the right to the city. According to a World Bank document titled "Transforming Karachi into a Livable and Competitive Megacity: A City Diagnostic and Transformation Strategy," about half of Karachi's population live in informal settlements and feel they have no right to the city but instead are stuck in a cycle of poverty. Although they may not have rights to some parts of the metro city, they have the numbers to influence voting outcomes and this encourages political parties to implement utility services and beautification projects in some katchi abadis. More often though, the interests of mega-rich global corporations win out. The rights to streets, ancestral lands, and settlement lands are a consequence of a densely populated globalized city with its own distinctive ethnic and sectarian social divisions and economic inequality.

Walking in the City video note: the thumbnail image is not Karachi, however, the video is.