Vernacular and Transnational Urbanism

In Vernacular Architecture by Henry Glassie about vernacular versus transnational architecture, vernacular urbanism is not a term specifically used, but one can glean the meaning from the book reading. Vernacular architecture seeks to understand how culture and local resources determine the look and function of human homes and building structures. Vernacular urbanism represents the stroke of humanity on nature’s canvas, as exemplified in a log cabin in the forest. Every region has material clues to show its time period; the further the materials traveled, the cleaner the lines, the more assured you become that this impersonal habitat is contemporary with transnational design. Local materials denote a structure from the past; rustic, organic, and jagged; architectural lines as uneven and imperfect as humanity itself. The exception to this architectural timeline is a self-built shantytown, vernacular and ephemeral in nature. Vernacular urbanism is local and personal, built up from the community that inhabits it with materials and design native to the land.

Transnational urbanism is made up of structures that are monumental and impersonal. No sign of human life can be seen from these sky-scraping buildings with clean lines and smooth surfaces. The reflection of your face as you walk past one is the only hint of humanity these buildings give from the outside. Most people do not live in structures such as these. The materials used are not recognizable as coming from nature and are very likely globally sourced. These buildings block views of the natural landscape. More importantly, many sit atop the ghosts of past cultures, economies, and communities. These ghosts are reminders that this is a powerful structure outpacing our upward gaze as if it is a steel and glass deity that we must serve. In Eric Darton's 1999 article The Janus Face of Architectural Terrorism, transnational architecture and urbanism is also not specifically defined but the reading draws on the World Trade Center (WTC) in New York as an example of what this means. The WTC towers emerged out of the ground pushing out hundreds of years of a maritime culture and economy. Towers so tall that everyone in the city could see them, yet the buildings give no indication that there are people inside. Darton compares the existence of these towers to the mental schema of terrorists. Seeing humanity as not flesh and blood, but as an abstraction. Eerily, two years later, terrorists took down the towers.

Transnational urbanism is the antithesis of vernacular urbanism. Vernacular architecture represents people, culture, humility, and local resources. Transnational architecture represents modernity: sterile, monumental, commanding, and industrious. One must remind oneself that both architectural developments are designed by humans and for humans. Vernacular architecture functions as homes, churches, places for community, whereas transnational architecture functions as a place where people work, often for global companies, or reside in luxury residential towers. In a vernacular structure, a person feels powerful and in control of their environment. In transnational structures, a person feels powerless and disconnected from their environment. Both forms of architecture and urbanism exemplify creative destruction in that their development depends on the destruction of a natural habitat or pre-existing structures. Land is cleared and materials extracted from nature, for there is often destruction in preserving the existence of mankind.

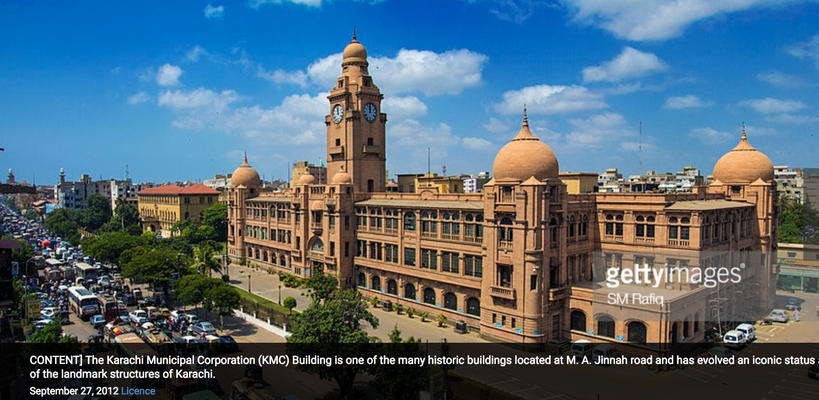

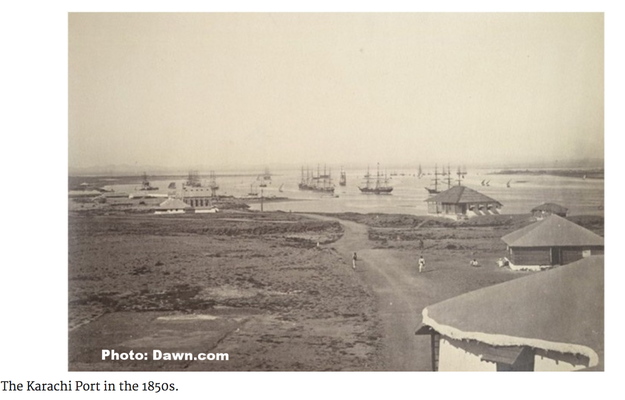

In Karachi, there are many examples of vernacular and transnational architecture. The katchi abadis that make up the informal living sector are vernacular in architecture as they are built and inhabited by the locals. Many street vendors make up the informal economy and is an example of vernacular urbanism. Contrast the informal economies with the transnational shopping malls selling high end brands from all over the world. Transnational urbanism has found its way into the city through these upscale malls as well as corporate towers, luxury high rise living spaces, and European style masterplanned communities.

Applying what we have just learned about vernacular versus transnational architecture and urbanism; in the images below, does the left side appear to be vernacular and the right side transnational?